The Case

This chair was purchased in 1988 for $6,000 as a genuine Windsor fan-back armchair from 1780−1800. At that time, outstanding examples of such chairs could sell for $10,000 to $50,000, so this one seemed to be a bargain. When fellow collectors questioned its authenticity, however, the owner took the seller as well as the “picker” who allegedly found it to court. A grand jury indicted the pair on charges of theft by deception and criminal simulation.

Three experts examined the chair but disagreed on the date and attribution. One thought it was five to ten years old and worth maybe $500. A second expert considered it to be a copy of a Wallace Nutting chair dating from the 1920s or 1930s. The opinion of a third expert, a dealer, was that it dated to between 1830 and 1850 and was worth $3,000 to $4,000.

Who was Wallace Nutting?

Wallace Nutting was a Key Figure in the Colonial Revival, which peaked in the early 1900s. The movement was characterized by its romanticized vision of early American values and objects, especially home goods. Nutting ran a thriving business making and selling reproduction early American furniture. His products were not intended to deceive and were clearly marked with his stamp. Today Wallace Nutting pieces have also become collectors' items.

Photo of Wallace Nutting

John Keep Nutting, Nutting Genealogy: A Record of Some Descendants of John Nutting of Groton Massachusetts, Syracuse, N.Y.:, C.W. Bardeen Publisher, 1908.

The Verdict

The defendants argued that they could not be expected to accurately identify the chair in question if even the experts disagreed. The prosecution argued that they should not have represented the chair with a specific attribution if they were not certain. The defendants were acquitted.

Later evaluation at Winterthur clearly showed that the chair was made in the early 20th century by Wallace Nutting, a maker of reproduction furniture. It had been modified by someone, however, so that it appeared to date to the late 18th century. The Nutting brand had been removed from the seat bottom, and several layers of modern paint had been added with the intent to deceive.

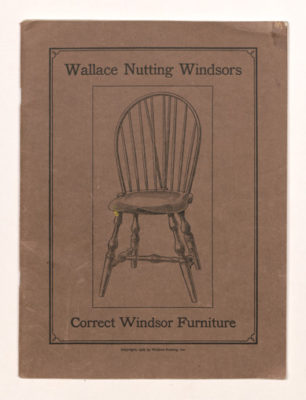

This Wallace Nutting trade catalog from 1918 displays examples of Nutting's work, and it can be found in the Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection.

Wallace Nutting Windsors: Correct Windsor Furniture (Sougus Center, Mass.: Wallace Nutting, Inc., 1918.)

Winterthur Library, Printed Book and Periodical Collection

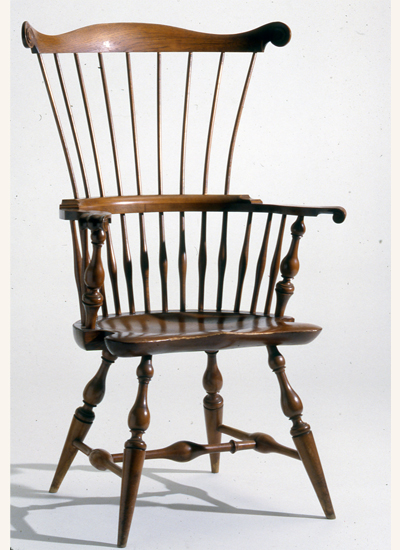

Compare the shape of the chair on the left, the subject of the trial, with a genuine early 20th- century reproduction created by the firm of Wallace Nutting (on the right). Although the form is clearly the same, there are many differences. The example on the right retains its original varnish while the other has been painted red and green to imitate an original and then artificially distressed. The chair from the trial is shorter because the partial holes drilled to attach the legs were extended through the top of the seat. How many other differences can you identify?

Fan-back Windsor armchair

Made by Wallace Nutting; 1925−30

Maple, oak, pine, painted and distressed

Gift of Burton W. Pearl M.D. 1989.26

Wallace Nutting used a heated iron brand to burn his maker’s mark deep into the seat of the chair on the right to ensure that his reproduction furniture was not mistaken for genuine antiques. The seat of the chair from the trial is much thinner; the bottom had to be shaved down to completely remove the brand that was once present.

Bibliography

Denenberg, Thomas Andrew. Wallace Nutting and the Invention of Old America. New Haven: Yale University Press in association with the Wadsworth Atheneum, 2003.

Eaton, Linda. “With No Intention to Deceive: Wallace Nutting on Fakes and Reproductions.” Winterthur Magazine 44, no. 1 (Spring 1998).