Weathering in Vane?

Weathervanes have always been both aesthetically pleasing and utilitarian objects. They are placed on the tops of buildings to indicate wind direction, but their shapes are decorative, often celebrating political, agricultural, or even sporting achievements or occupations. Today collectors of folk art appreciate the aesthetic qualities and value particular forms, surface appearance, and rarity. Vanes are made by pounding copper sheeting over a wooden or metal mold to create the two sides, which are soldered together. Most authentic vanes have split seams and repairs. Because genuine vanes would have spent decades exposed to the sun and weather, issues of authenticity often relate to the appearance of corrosion on the surface. Although original owners would often re-paint or re-gild these surfaces when they began to corrode, today’s collectors value the patina of age.

Provenance

Weathervanes rarely have any provenance. The only way to be sure that you can connect one to its original location is to have a photograph of it in situ. Even then, there has to be a specific detail that is clearly visible in order to make a positive identification. Weathervanes have been collected since the early 20th century, so those that have belonged to important collectors or have been sold at public auction can acquire a recent history. Few, however, can be traced back to their original placement. Fakes of original vanes have been in circulation since the 1970s, so it is best to investigate their history prior to that time.

Archangel Gabriel

The Archangel Gabriel was a popular figure for American weathervanes, and many versions have survived from the 19th century. The identification of a synthetic resin in the sizing layer beneath a brass, rather than gold, leaf proves this is a fake. The dents were probably made by a BB gun and were shot straight at the vane instead of from below―an indication that they, too, are fake.

Archangel Gabriel weathervane; 20th century

Copper, brass leaf

Private collection

Connoisseurship

Weathervanes were often used for target practice, and collectors sometimes value bullet holes as evidence of age and legitimate use. The dents on this piece, however, were probably produced by a BB gun, as real bullets would have penetrated the copper. The direction of the dents indicates that the pellets were shot straight, at the level of the vane. Because weathervanes are found on the tops of buildings, a genuine hole or dent created by a bullet should be at an angle, since the bullet would have been shot from ground level. The edges of the hole would have thinned over time as well. The form of this vane is similar to one featured in an 1883 catalogue for A.B. & W.T. Westervelt, a firm in business at 102 Chambers Street in New York City. The simulated damage, however, is a cause for concern.

Scientific Analysis

The surface was identified as brass leaf rather than the more usual gold leaf. Of greater concern, the sizing layer beneath the leaf was identified as polyvinyl acetate, a synthetic resin that was not invented until 1912. The brass leaf was applied to this sizing when it was wet and would turn black when exposed to the elements. The green corrosion layer was found to be copper chloride (atacamite), which is consistent with natural ageing in coastal towns due to salt spray. The lack of copper sulfates suggests that it was patinated with an acid treatment.

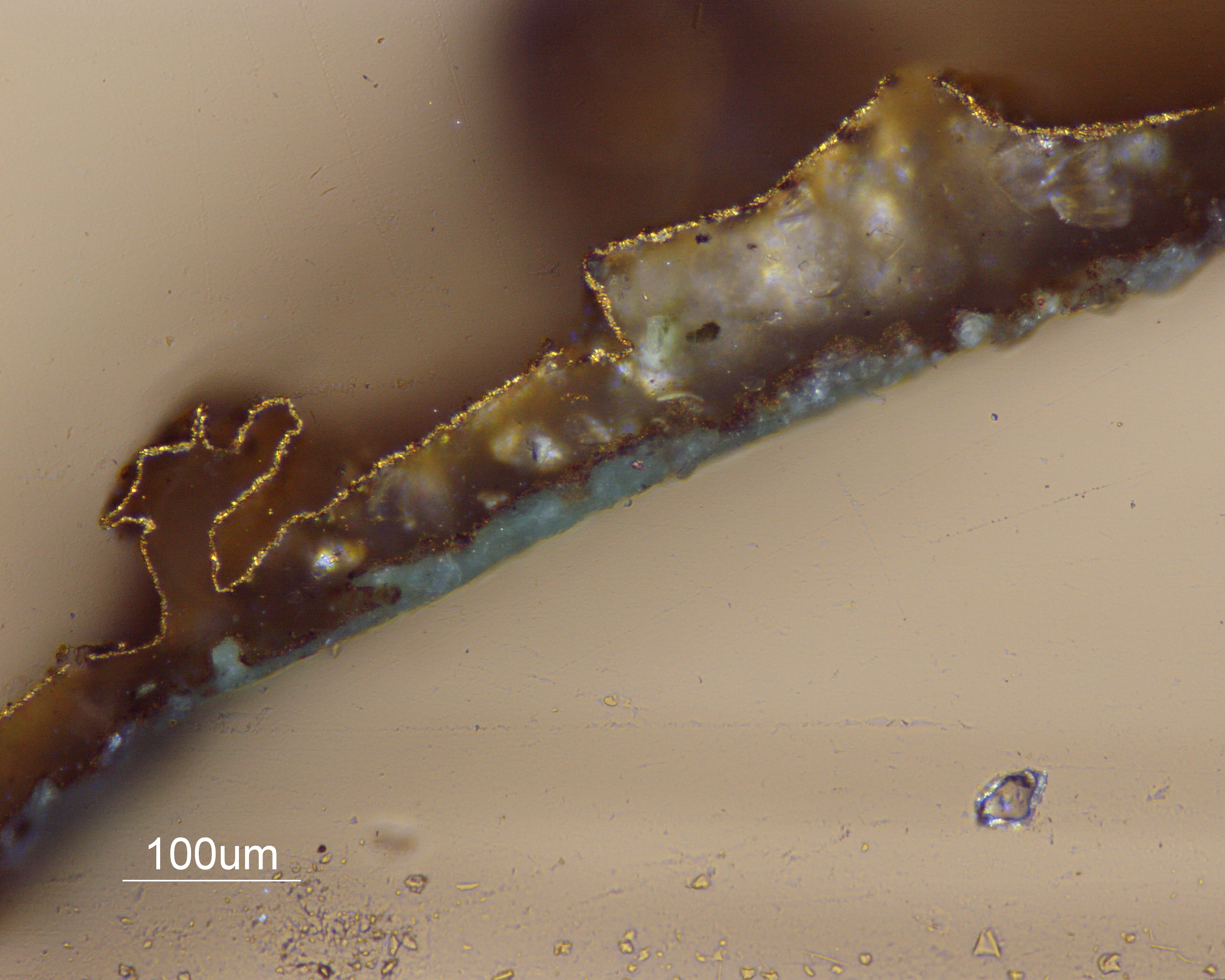

This cross section shows that there is just one layer of surface finish on the Archangel Gabriel weathervane in both visible and ultraviolet light. All you can see is one very thin layer of brass leaf on top of a thicker layer of a modern synthetic resin (polyvinyl acetate). A genuine weathervane would normally have been resurfaced many times, so the presence of only one surface finish is a cause for concern.

Scientific Analysis of Fine Art, LLC

Verdict

The copper chloride patina; the 20th-century materials used to gild the surface; and the lack of any copper sulfates in the surface strongly suggest that this vane was patinated with an acid treatment with the intention to deceive. The dents simulating damage from bullets confirm this conclusion.

Goddess of Liberty

This is a close copy of a vane created originally by A.L. Jewell & Company of Waltham, Massachusetts, which was in business from 1852 to 1867. After Jewell’s death, the firm was acquired by Cushing & White (later L.W. Cushing & Company and L.W. Cushing & Sons), which continued to produce the same designs. The Goddess of Liberty was a popular design, especially in the 1880s, when the then-new Statue of Liberty created a fashion for related versions.

The Goddess of Liberty, sometimes known as Lady Liberty, was a popular form for weathervanes in the 19th century. Often a mold is taken from an original vane, so a fake will usually be slightly larger in size. Look closely at this form. Do you think it shows normal signs of age?

Goddess of Liberty weathervane; 20th century

Copper and zinc

Private collection

Connoisseurship

The green surface is common for weathered copper, and the white sash and hatband appear to be zinc, like genuine examples. The problem is that the form is too sharp; it does not display the softening and distortions that would be expected in a weathervane of this age.

Scientific Analysis

The green corrosion layer was found to be a copper sulfate compound, brochantite, which is commonly found in naturally aged copper and bronze and indicates a naturally aged surface.

Verdict

In this case, the scientific analysis found nothing wrong, but connoisseurship identifies this as a fake. It was probably made from period copper roofing materials, a practice known to have been used to create other fake weathervanes.

Connoisseurship

Many famous racing horses were commemorated in weathervanes in the late 19th century, often copied from popular prints of the time. The presence of a rider is rare and would have made the vane more expensive than one with just a horse alone. It is the fence, however, that is the anomaly here; it makes the vane even rarer and is cause for concern.

Analysis

XRF analysis identifies that the horse and rider are made from copper, but the fence is made of brass (a copper and zinc alloy). The green corrosion layer of each component was sampled and analyzed using FTIR and XRD. The corrosion layer of both horse and rider is brochantite, the most usual type of natural corrosion found on copper surfaces. The surface finish of the fence, however, was identified as rouaite, a copper hydroxyl nitrate that would have been produced by treating the surface of the brass with nitric acid. A simulated verdigris surface will disintegrate if exposed to the elements; if displayed outside, the fake surface will wash off within a year.

Verdict

The different material and surface finish for the fence strongly suggest that it was added later to the original vane that depicted just a horse and rider. The intent was to increase the monetary value of the weathervane.

Bibliography

Lindberg, Julie, and Jennifer L. Mass. “Weathervane Finish Analysis.” AFA News, September 6, 2011. http://www.afanews.com/articles/item/852-weathervane-finish-analysis#.WFrBarYrL2Q