All that Glitters . . .

Arthur Lenssen (1874−1968), a successful New York businessman, began to collect antique American silver in 1930. At first he purchased primarily through auction houses and reputable dealers, but from 1934 onward he began to rely on two dealers from Philadelphia, Samuel Harris and Albert Morley.

Lenssen’s first purchase from Harris, in 1934, was a small, genuine antique tablespoon made by Samuel Vernon; it cost $20. Over time, Harris and Morley supplied more expensive objects purportedly made by prestigious early American silversmiths.

Questions were asked about the authenticity of many of the pieces in the Lenssen collection when it was being appraised at the request of the Stevens Institute, to whom it was bequeathed.

Provenance

Arthur Lenssen kept careful records of where he purchased his collection and what he paid for each piece. His ledger books show that he bought nearly 280 objects from Philadelphia dealers Samuel Harris and Albert Morley over a period of fifteen years. An astonishing 90 percent of the fakes found in Lenssen’s collection came from those two dealers. Clearly Harris and Morley were part of a consortium of fakers that included, at the very least, a skillful silversmith, an engraver, and a die maker.

Ledger book

Wunsch Americana Foundation

Connoisseurship

The authenticity of many of the pieces in the Lenssen collection only came under question when the silver was being appraised. Most early American silversmiths marked their work; close examination of many of the marks in the Lenssen collection were found to be spurious. Questions were also raised concerning the style of pieces purportedly made by particular silversmiths as well as the methods of fabrication and evidence (or lack) of wear. Other problems that were identified include mistakes in attribution, some of which may have been unintentional, as well as objects that had been repaired or re-made with an obvious intent to deceive.

Research on the Lenssen collection was conducted at Winterthur. Examining, analyzing, and evaluating the results on the more than 1,000 pieces took some three years.

Janice H. Carlson, former Senior Scientist (left)

Donald L. Fennimore Jr., former Senior Metals Curator (right)

Objects Lab, Winterthur Museum

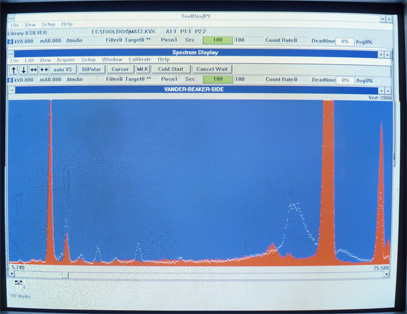

This is a photograph of a spectrum displayed on a computer monitor in the 1980s, which is why it looks very different from other examples in this exhibition. The analysis, however, is still valid.

Scientific Research & Analysis Laboratory, Winterthur Museum

Scientific Analysis

A new method of analysis developed at Winterthur in the 1970s uses energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) to identify the various elemental components of silver alloys. Silver refined before the mid-19th century contains trace amounts of gold and lead. The absence of these elements identifies silver as being refined after about 1850. XRF analysis can also identify pieces made in whole, or in part, from English or Continental silver, which have a different level of purity than American silver.

The solid red spectrum is from the Vander Burch beaker, and the dotted white line is from a genuine 17th-century beaker, showing the presence of gold and lead (small peaks, at arrows). Before the mid-19th century, all silver contained trace amounts of gold and lead. After that time, advances in metal refining technology facilitated the removal of almost all such traces. Modern silver, therefore, does not show signs of these elements.

Verdict

Scientific analysis has confirmed the observations made by careful connoisseurship: 75 percent of the Lenssen collection has been found to be fake and most, but not all, of the fakes were sold by Samuel Harris and Albert Morley. Because the fakes were only identified after the death of Arthur Lenssen, no one was ever charged for these crimes. Sadly, a fair amount of spurious early American silver can still be found on the market.

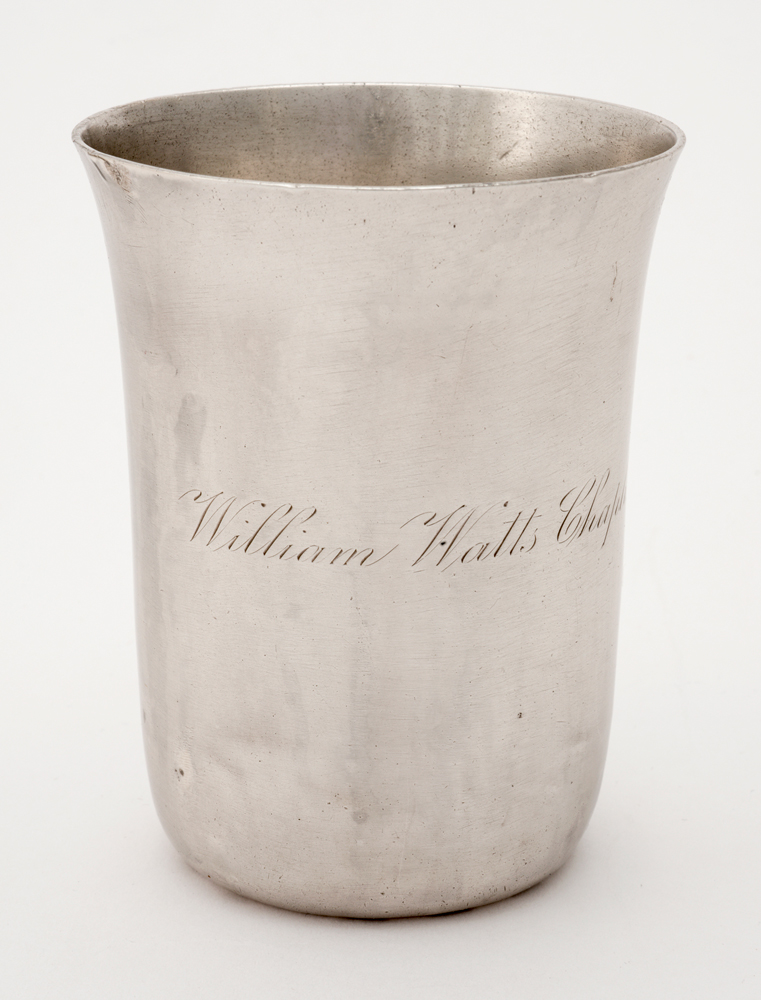

The Vander Burch Beaker

Was the beaker that Arthur Lenssen purchased really made by Cornelius Vander Burch, a prominent late 17th-century New York silversmith? It is almost an exact copy of "the most impressive piece of early American silver" in the Mabel Brady Garvan Collection at Yale.

If you compare it to the genuine beaker on the left, you can see that the engraving on the purported Vander Burch is heavy-handed, with a misunderstanding of certain design elements. The beaker has no known history of ownership before its purchase by Arthur Lenssen. XRF analysis provides evidence that the beaker is made from modern silver.

Fake beaker (right)

Purported to be made by Cornelius Vander Burch

Probably sold by Albert Morley

Philadelphia, Pa.; 1930−50

Wunsch Americana Foundation

Genuine beaker (left)

Made by H. H.

New York or Albany, N.Y.; 1680−1710

Museum purchase with funds provided by Henry Francis du Pont 1958.95.1

Three Clues Tell the Truth

Compare the Vander Burch beaker, a fake (right), with a genuine 17th-century beaker (left). Three distinct clues can be seen.

-

Hammer marks are clearly visible on the Vander Burch beaker. On the genuine beaker, these marks (the result of raising the beaker from one sheet of silver) were smoothed out by the maker and have been further reduced by 300 years of handling and polishing.

-

The edges on the rim and engraving of the Vander Burch beaker are sharp. Compare these with the softer, worn edges of the genuine piece, which are the result of generations of handling and polishing.

-

The lines of engraving on the genuine beaker change in thickness and depth. The engraving on the Vander Burch beaker is awkward by comparison.

Verdict

This beaker is an outright fake made with the intent to deceive.

Paul Revere Silver

Silver made by patriot and Revolutionary War hero Paul Revere is highly prized by collectors. After acquiring a genuine Revere porringer, Arthur Lenssen wrote that the purchase “put him on the map” as an important collector. Yet, in nearly every case, objects attributed to Paul Revere in the Lenssen collection raise a variety of questions relating to style, wear, maker’s marks, and composition.

Genuine Revere porringer

Arthur Lenssen purchased this handled bowl, known as a porringer, at auction in 1931 for $2,300. An article in the New York Sun listed the names of the purchasers from that sale as well as the prices they paid. The publicity identified Lenssen as an important collector and probably attracted the attention of the unscrupulous dealers Samuel Harris and Albert Morley.

Sold by American Art Association

Genuine Revere mark

Wunsch Americana Foundation

Fake Revere porringer

Analysis shows that the handle on this porringer is made from modern silver. Compare the engraved letters on the two porringers. Notice how sharp and heavy the engraving is on the handle of the fake and how soft and round the worn edges of the mark on the genuine engraving look.

Sold by Samuel Harris

Revere mark added 1930−50

Wunsch Americana Foundation

Spoons

Makers’ marks identify which individual or workshop produced a piece of silver. Variations in the way a mark is struck onto an object can result in superficial visual differences. Experts look for uniformity of small details to determine whether a mark is genuine or fake. Paul Revere used several marks during his long career, making attribution particularly challenging.

In the first image, the spoon at the top of this group of three is genuine. The other two spoons are made from old silver, but the makers’ marks are modern copies of the mark on the genuine spoon.

XRF analysis of the spoon in the second image indicates that it is made from old silver. The form is typical of a genuine 18th-century spoon. The mark, however, does not match any known genuine or fake Revere marks. It might be genuine, but we cannot tell for sure.

In the third image, he teaspoon (top) is made of old silver with a genuine mark. XRF analysis proves that the salt spoon (bottom) is made of modern silver. The Revere mark on the salt spoon must therefore be fake, although it is an excellent copy of the mark on the teaspoon.

Shoe Buckle

This buckle is a genuine 18th-century piece. The Revere mark, however, was struck with a die made in the 20th century.

Fake Revere shoe buckle

Sold by Samuel Harris

Revere mark added 1930−50

Wunsch Americana Foundation

Fake Revere Candle Snuffer

XRF analysis shows that this snuffer is made from silver refined before 1850. The lack of distortion and wear as well as the clumsy design of the components, however, suggest that the piece was made in the 20th century from old silver.

Fake Revere candle snuffer

Sold by Samuel Harris

Revere mark added 1930−50

Wunsch Americana Foundation

Fake Revere Beakers

Although XRF analysis shows that this beaker is made from silver refined before 1850, the form is recognizable as post-Revere. In addition, on genuine pieces the engraved border would normally have been placed on the outside of the lip, not the inside. The mark matches others identified as fake. It was added in the 20th century to a 19th-century beaker to enhance its value.

Fake Revere beaker

Sold by Samuel Harris

Revere mark added 1930−50

Wunsch Americana Foundation

XRF analysis demonstrates that this beaker is made of modern silver. The Revere mark, therefore, must be fake. Look closely at the surface of this piece for the evenly distributed chinks and dents. A genuine piece would exhibit uneven wear.

Fake Revere beaker

Sold by Samuel Harris or Albert Morley

Revere mark added 1930−50

Wunsch Americana Foundation

Sugar basket of questionable origins

Tests of authenticity of this sugar basket are inconclusive. Although XRF analysis provided qualitative evidence that the silver is old, quantitative findings suggest that the silver content of this piece is higher than that generally found in American silver. English regulations for sterling required at least 92.5 percent silver. The average silver content found in late 18th-century American hollowware is only about 90 percent. This basket is probably a 19th-century English piece that was not marked or whose original marks were removed.

The engraved date reads 1866, but it may have been added later; therefore, it does not necessarily represent the date the object was made.

Bibliography

Carlson, Janice H. “The Stevens Institute Silver Collection.” Analytical Report #1372, April 22, 1983 (unpublished report, Winterthur).

Carlson, Janice, and Donald L. Fennimore. “The Fakes.” Indicator: Magazine of the Stevens Alumni Association 100, no. 4 (Winter 1983): 4−13.