Genuine Fake

John Myatt (b. 1925), a relatively successful artist and teacher who could not earn enough to support his children, devised a plan to sell “genuine fakes” and advertised in a local paper, which is not illegal. He later teamed up, however, with John Drewe, who posed as a wealthy collector to gain access to important museum archives and gather information to make Myatt’s fake paintings more believable. Drewe stole documents that he subsequently altered and also added information to crucial files that collectors and curators rely on as proof of the authenticity of works of art. When Scotland Yard investigators raided Drewe’s home, they seized the typewriter, stolen documents, and counterfeit stamps he used to create his fake, but convincing, provenances. Eventually, the sheer number of previously undiscovered masterworks he sold caused suspicion. Investigation by the Art & Antiquities Unit of Scotland Yard resulted in a trial in 1999.

The Verdict

Myatt admitted he sometimes created “appallingly bad” imitations, but Drewe’s clever manufacture of false provenances turned Myatt’s dubious paintings into masterpieces that went unquestioned. Convicted of forging more than 200 modernist paintings over seven years (about 120 of them are still circulating in the art market), Myatt received a prison sentence of one year. Drewe, considered the mastermind behind the fraud, received a sentence of six years. Today John Myatt’s artwork is in great demand and commands high prices. His notoriety has earned him invitations to lecture, teach at prominent universities, and appear on television.

For his forgeries, Myatt did not try to obtain historically accurate materials. He often relied on common house paint and rubbed the canvas with coffee grinds and vacuum-cleaner dust to artificially “age” the works. Myatt’s trick for achieving the right consistency of oils—without the expense of oil paint—was to mix KY ®Lubricating Jelly into acrylic or vinyl-based paints. Myatt prefers to work in a green painter’s apron he has worn for years.

John Myatt’s apron, tools, and materials from his studio; ca. 2013

Collection of Colette Loll; photo, courtesy of Ak Suggi

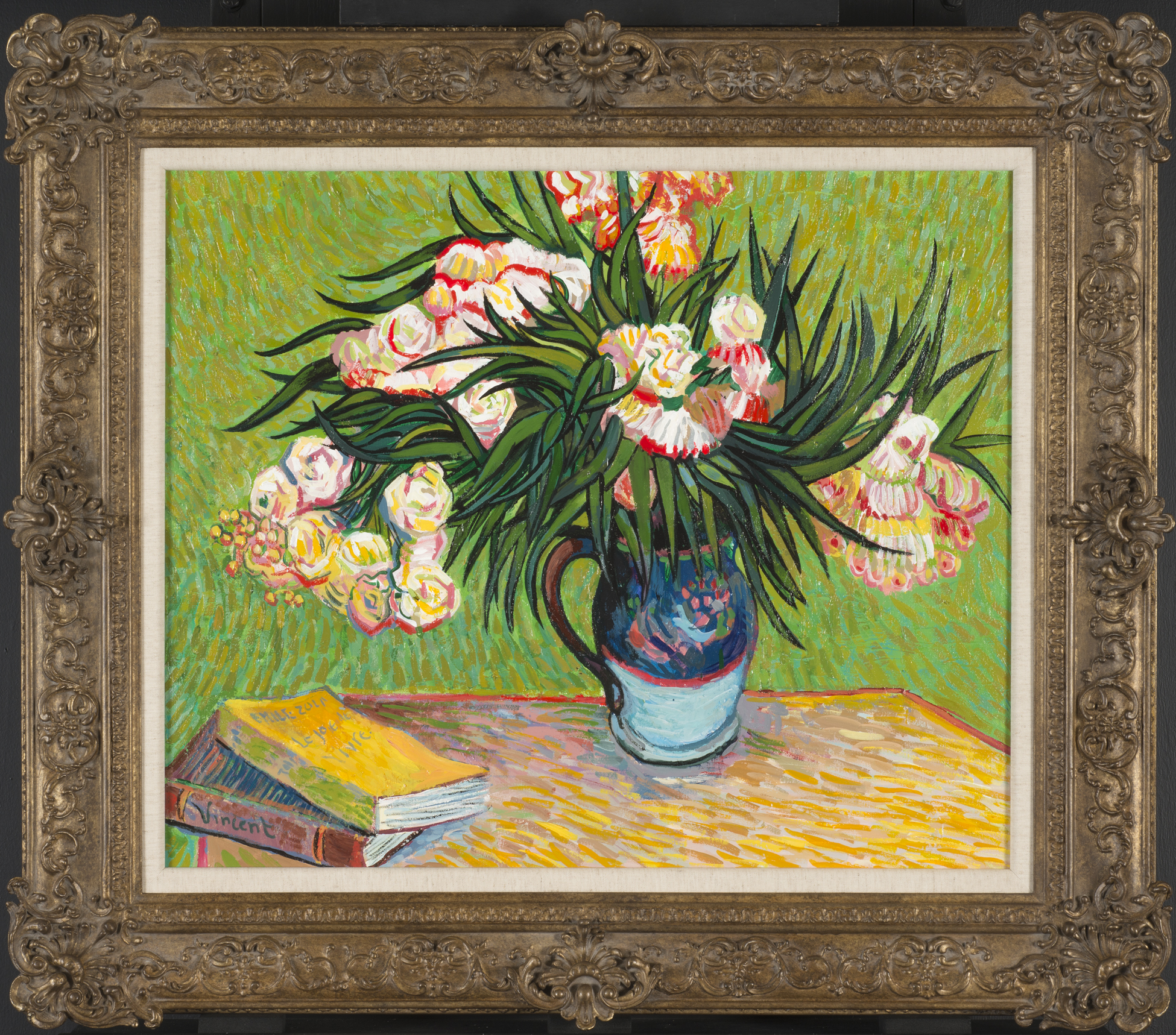

Released from prison for good behavior after serving only four months, Myatt was encouraged by Jonathon Searle—the police officer who arrested him—to redeem himself by selling “genuine fakes” like this work in the style of Vincent Van Gogh (1853−1890). Myatt has now become a celebrity, but he stays on the right side of the law. Each artwork he creates is clearly signed so it can never be sold as authentic.

The original Oleanders, by Van Gogh, hangs at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The flowers fill a majolica jug that the artist used for other still lifes he created in Arles, France, where he spent a great deal of his career. How convincing is John Myatt’s copy?

Copy of Oleanders, after Vincent Van Gogh John Myatt; 2012

Oil on canvas

Courtesy of Washington Green Fine Art

Bibliography

Salisbury, Laney, and Aly Sujo. Provenance: How a Con Man and a Forger Rewrote the History of Modern Art. New York: Penguin Books, 2010.