Fake Philately

Since the mid-1800s, stamp collecting (philately) has ranked among the world’s most popular hobbies. England introduced the world’s first postage stamp, the Penny Black, and by the mid-1860s most industrialized countries were issuing postage stamps of their own. Stamp collecting occurred as early as the 1850s, but many stamps were rare, expensive, or difficult for people to acquire. Replicas/facsimiles therefore became popular, especially among younger collectors.

It is in this context that Spiro Brothers, a prominent lithographic firm in Hamburg, Germany, began to replicate international postage stamps. It proved to be a lucrative business. The firm printed approximately 500 different types of stamps over a period of fifteen years. Information about their replicas has been widely published since the 1870s, but even serious collectors can sometimes be fooled, particularly if the replicas have been modified with the intention to deceive.

Provenance

Stamps rarely have any provenance unless they have been owned by an important collector. Nothing is known about the history of ownership of these stamps.

Connoisseurship

Although the Spiro Brothers facsimiles made no major alterations to the image, the company used a different technique to print them. Genuine stamps were engraved, but the forgeries are lithographs. Another difference is that the forgeries do not have gum on the back. The perforations on the originals are sharper, due to the stiffening effect of the gum. Although fake stamps can sometimes be identified through differences in the paper, the Spiro Brothers created these facsimiles soon after the originals were issued, so the paper is similar.

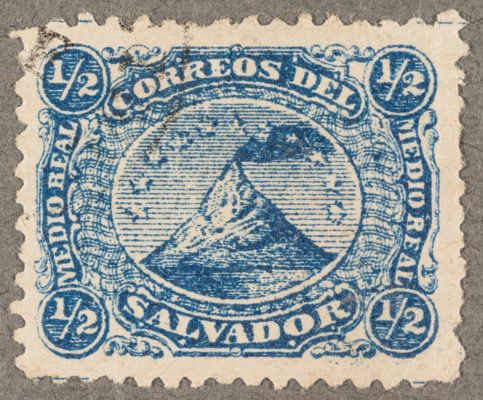

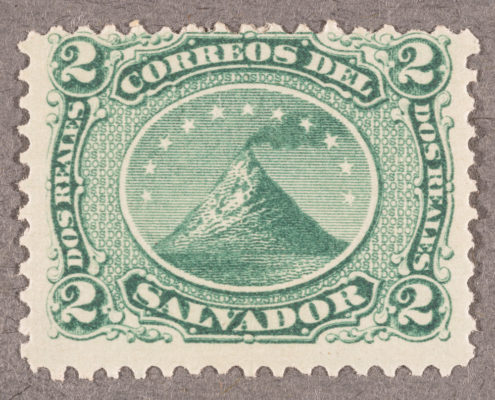

San Salvador issued its first stamps in 1867. They depicted the Izalco volcano in the west of the country. Different values were distinguished by color; blue was worth ½ a real (8 reales in a peso), and green was worth two reales.

The two stamps on the left were counterfeited by the Spiro Brothers in the first few years of their issue (1867). Originally printed in sheets, which could be purchased with or without perforations but always without glue on the back, the stamps have been separated and sold as genuine to an unsuspecting collector. The stamps displayed on the right are genuine.

Photomicrographs

Paper Conservation Laboratory, Winterthur Museum

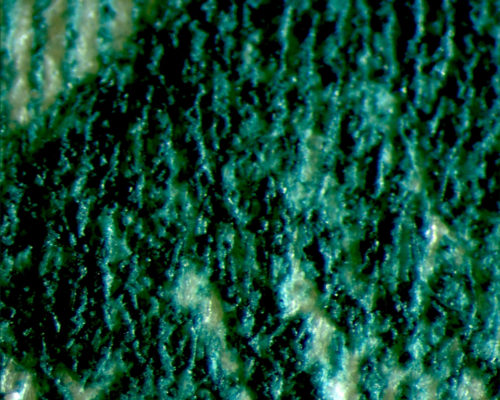

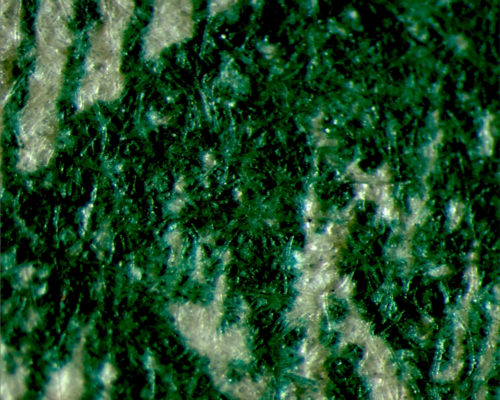

If you look closely at these two micrographs, you can see that the genuine stamp looks more three-dimensional than the replica stamp. This illustrates two different printing techniques. The design of the genuine stamp is cut into a metal plate, a technique known as engraving. The plate is inked and then run through a rolling press under high pressure, leaving a three-dimensional impression on the paper. The replica is printed by lithography, a process based on the principle that water and oil do not mix. The printer draws a design on a stone with an oil-based crayon, making the inked areas water repellent and the non-inked areas water absorbent. After printing, the surface of the paper remains completely flat.

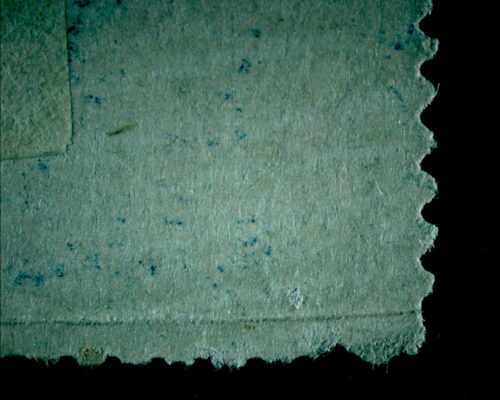

These two photomicrographs show the back of the stamps. Can you see the glare and yellow color caused by the gum on the genuine stamp? Another difference is the regularity of the perforations, the result of the paper being stiffer from the gum/glue. The edges of the perforations on the replica/fake are less sharp.

Verdict

The stamps made by the Spiro Brothers are replicas, but they did not intend to deceive. In later hands, however, such replicas have often been sold as genuine by unscrupulous dealers out to fool unsuspecting collectors. Even some sophisticated dealers have mistaken Spiro Brothers facsimiles for the real thing.

Bibliography

Atlee, W. D., E. L. Pemberton, and R. B. Earée. The Spud Papers, 1871−1881: An Illustrated Descriptive Catalogue of Early Philatelic Forgeries. Lucerne, Switz.: Emile Bertrand, 1950. http://stampforgeries.com/spud-papers/

Lera, Thomas. The Use of X-Ray Fluorescence in Detecting Philatelic Forgeries. Institute of Analytical Philately, March 28, 2015.

Maassen, Wolfgang. “The First ‘Forgers’: Philip Spiro, Hamburg.” Fakes, Forgeries & Experts Journal 13 (2010). http://www.ffejournal.com/articles.php?book=FFE+%2313